Listening to Yourself

Image Description: A close-up from an ink sketch self portrait of a woman’s eyes and nose. Image courtesy of the author.

OK, well first you have to listen to me. But I promise this personal story will ultimately come back to you.

As you know from an earlier blog post, one of my goals this year was to transform a room full of stuff into a creative sanctuary. While my timeline for completion has extended (living example that goals are intended to adapt to life’s realities), I have continued the process slowly but surely. A few days ago, I unearthed a treasure trove of sketchbooks that I had kept in those years when I was transitioning from high school to college to young adulthood.

One of the earliest of these finds was a sketchbook that I had apparently used as an essay for an art school scholarship application. The instructions are pasted into the inside page of the sketchbook and say: “Applications are to be accompanied by an essay in which the applicant addresses the following points: the applicant’s personal philosophy regarding the creative process, a characterization of the applicant’s role as an artist in relation to the history of art, and a definition of the applicant’s goals as an artist of the Twenty-First Century. The essay will be judged on its depth of treatment and workmanship.”

Wow, what a requirement! Looking back, it seems quite ludicrous to think that an 18 year old with little experience of life or the world would have developed a personal philosophy regarding the creative process. And yet here are a few excerpts of what I wrote, mixed in with some of my sketches and drawings and quotes from some famous artists and writers:

The one clear definition of art is that there is nothing clear or definite about art. Art has two faces. One is the expression of the artist. The other is, as beauty is said to be, ‘in the eye of the beholder.’ No viewer will ever see a work exactly the way the artist saw it. Art is created for interpretation.

To create something demands much thought, planning, choice, and repetition. Whether penning and essay or daubing paint on a canvas, the artist must follow a sequence to completion...From the rough draft or thumbnail sketch to the finished work, the creator relies on a complicated thinking process involving knowledge of far more than correct grammar or mix of colors. This knowledge, whatever the medium, is derived from the same source -- past experience.

Image Description: A page from the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. A colorful expressionistic painting of a face that could be a bald man or an alien.

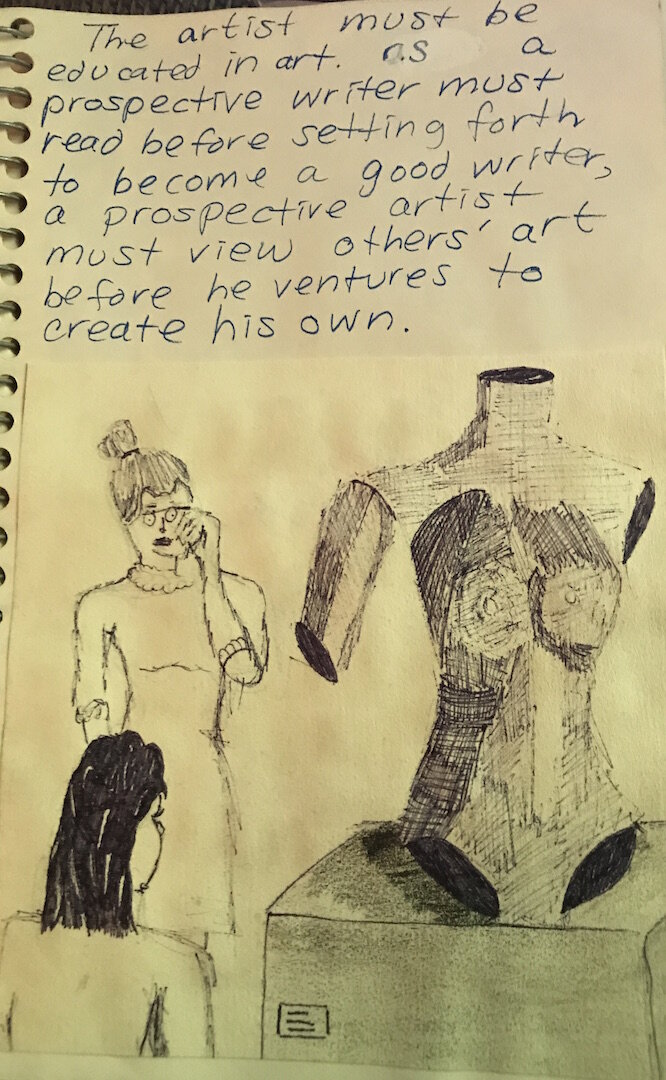

The artist must be educated in art. Much as a prospective writer must read before setting forth to become a good writer. A prospective artist must view others’ art before he ventures to create his own. The artistic experience is an enriched process of learning. Art adds depth because it focuses on hands-on intuitive learning -- quite different from that induced by reading lists and research papers.

It is impossible for any neophyte artist to judge his role in the history of art. Art is a lifetime process. At my age, I am still working towards a development of style by experimenting with different ones. I have enjoyed my encounter with cubism, dadaism, and expressionism. Yet I don’t want to be imprisoned in another person’s style. I would prefer to create my own -ism.

Image Description: A page from the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. It includes some of the text from above and a pen-and-ink drawing of two women (one of whom is wearing glasses) at a museum or gallery looking at a sculpture of a woman’s naked torso.

Art is created for:

Enjoyment

Need of the artist to create

Self-expression

Interpretation

Some might argue that the process of creation is more important than the finished product. While the process is essential, it is only as good as the finished product.The purpose of a time-consuming process is to produce a worthy result. If one of the steps in the process is not completed to the artist’s full potential, the finished product will reflect this lack of planning. The entire planning process is accomplished for a finished product. Planning reflects all of the reasons to create (except perhaps enjoyment) but the finished product should provide adequate enjoyment for the artist. The process is, therefore, necessary, but does not surpass the importance of the finished product. No matter how much planning goes into an artwork, only the completed work reflects the complete artist.

Image Description: A page from the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. A pencil drawing of a pair of scissors wearing ballet slippers. Text in the picture reads “Art is a dance through life.”

No matter how technically superior an artwork is, it must stand out in some way. Technical excellence means little without thought and creativity. A painting of a face is a painting of a face is a painting of a face. But how to make it exceptional? That is up to the individual artist. In fact, that is exactly what makes him individual. The artist must set himself apart from others. Anyone can show the obvious, but an artist must show the unusual. In some cases, to be less obvious, the artist must arrive at the most obvious solution.

Image Description: A page from the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. An illustration of how to turn a couple of intersecting lines that look like a “7” into a new drawing in obvious and less obvious ways. The obvious way is to turn the “7” into a “Z.” The less obvious ways are to turn it into a fierce dog’s ear or a person’s nose or eyelid.

I then referenced James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, one of the few books in high school English class that had really spoken to me:

Like [the main character of the book] Stephen Daedalus, I have sought definition of myself as an artist only to be faced with my own doubts. Stephen affirms that he does not wish to overcome his doubts and neither do I. Joyce often deals with characters who are breaking away from a spiritual paralysis and finding a new direction...Like Stephen, I have doubts about theology, ideology, and my own future. With so many choices in life, I have not yet directed myself towards a single goal. At the same time, I have made no effort to overcome my apparent lack of direction. Instead I intend to pursue my interests in art, writing, and international studies, and let these interests guide me.

Image Description: A page from the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. An ink self-portrait with a quote that says “Art is the study of past philosophies to create one’s own philosophy.” — Erica Ginsberg

Now I might argue with my 18-year-old self on a few of my dogmatic philosophies about the creative process that have since evolved. (Not to mention the fact that I was using “he” to refer to a generality of the artist and pretty much only quoted male artists and writers). At the same time, I am impressed by the spirited way that I responded to art and revealed my own artistic development.

The reason I share these excerpts in a blog about creative resilience is not to relive my glory days as a young artist. I share because I believe that, on our personal journeys as creative people, we sometimes lose sight of our core beliefs about why we do what we do. With a lifetime of jobs, relationships, achievements, mistakes, joys, disappointments, gains, losses, observations, and mostly mundane moments behind us, we rarely take the time -- or the courage -- to reflect in the way that we might have when we were coming of age. There is sometimes raw and audacious truth uttered in youth.

I don’t remember if I got the scholarship or not. I didn’t end up going to art school. I studied international relations undergrad, worked in that field while doing creative things on the side, then went to film school, and went back and forth working between film and filmmaker support efforts and managing international exchange programs. To this day, I have still not “made an effort to overcome my apparent lack of direction” and have just settled into the life of being what writer and artist Emilie Wapnick describes as a "multipotentialite" (check out her TED Talk on the subject below).

Now is also the time to listen to ourselves. Whether we need to do so by looking back at our ways of thinking from many years ago or delving deep into why we desire to create right now, we need to make sure that the time we make for our creative practice includes not only time to create but also to reflect. This also requires us to temporarily mute the distractions of outside voices and our own inner critics. Just as we are more likely to hear birdsong outside our windows when the rest of our world slows down, so too can we hear our own songs from within when we allow ourselves to slow down.

This sketchbook was just the tip of the iceberg of what I found in this box on the bottom of a bookshelf. I continued sketching ideas for another decade in notebooks filled with doodles, collages, jottings, paintings, recording of dreams, and sketches. It made me thrilled both to see them again and a little sad that I had not kept up the practice. Ironically I seem to have stopped sketching just before the start of the 21st century. But I focused on what this discovery taught me. This was on the final page of the sketch essay:

Image Description: From a page of the author’s teenage sketchbook essay. The page reads in bright green ink: “The Artist in the Twenty-First Century is yet to be revealed (as are the remaining pages of this sketchbook).”

And so, now that I am an artist well into the Twenty-First Century, a new personal sketchbook has been born. For what is a sketchbook but a way to tune in to and freely express our own creative impulses?

Now you may not have a sketchbook to look back on. Perhaps instead you kept a journal. Or took photos. Or have a drawer or a file or a box or a pile with essays or doodles or various jottings you’ve not seen in years. Whatever fossils may be unearthed from your creative past, take a look at them and see if you are able to reconnect with their essence to help reignite your creative practice today.

If you stumbled upon this blog entry on the Internet or got it from someone else forwarding you a link, please consider signing up for Erica Ginsberg’s mailing list so that you will get the next entry in the Creative Resiliency series right to your Inbox. New entries are sent approximately once a month, and I do not share or sell contacts.